Develop with .NET on Ubuntu¶

This tutorial provides basic guidance on how to use the .NET toolchain for development on Ubuntu. It shows how to create a ‘Hello, world!’ program and how to create, build, test, run, and publish .NET projects using the dotnet command-line interface (CLI).

For instructions on how to install .NET and related tooling, including the .NET SDK, see the dedicated guide on How to set up a development environment for .NET on Ubuntu. This article assumes that tooling suggested in that article has been installed.

The .NET CLI¶

The dotnet command can handle multiple installed .NET SDKs and runtimes. It selects the right version of the .NET SDK or runtime when invoked. This has the advantage that you can use one command to interact with multiple versions of .NET.

Any .NET SDK provides sub-commands including new, run, build, and publish, which we use to develop the ‘Hello, world!’ application.

Run dotnet --help to see all available sub-commands.

Creating a .NET project¶

Create a directory where the project should be located and change into it:

mkdir "HelloWorld" && cd "HelloWorld"

Use the dotnet new command to create a .NET project from a template. Select the programming language of the project:

Run the following command to create a ‘Hello World’ console application written in C#:

dotnet new console

This creates the following files:

Program.cs: C# application code. C# source files usually have the.csfile extension.HelloWorld.csproj: This is the C# project file. C# project files usually have the.csprojfile extension.objdirectory: This directory is used to store temporary files used in order to create the final build output. Because it just contains temporary files, it is safe to delete and should be omitted from your version control system. You can ignore this directory for the rest of this article.

Run the following command to create a ‘Hello, world!’ console application written in F#:

dotnet new console -lang F#

This creates the following files:

Program.fs: F# application code. F# source files usually have the.fsfile extension.HelloWorld.fsproj: This is the F# project file. F# project files usually have the.fsprojfile extension.objdirectory: This directory is used to store temporary files used in order to create the final build output. Because it just contains temporary files, it is safe to delete and should be omitted from your version control system. You can ignore this directory for the rest of this article.

Run the following command to create a ‘Hello World’ console application written in Visual Basic:

dotnet new console -lang VB

This creates the following files:

Program.vb: Visual Basic application code. Visual Basic source files usually have the.vbfile extension.HelloWorld.vbproj: This is the Visual Basic project file. VB project files usually have the.vbprojfile extension.objdirectory: This directory is used to store temporary files used in order to create the final build output. Because it just contains temporary files, it is safe to delete ans should be omitted from your version control system. You can ignore this directory for the rest of this article.

Tip

Run the following command in a terminal to see a list of available templates:

dotnet new list

Tip

If you use git(1) as you version control system, you can generate a .gitignore file for .NET projects by using the template with the same name:

dotnet new .gitignore

Running the .NET project¶

Let’s see the application in action. Use the dotnet run command to restore dependencies (if we would have any), build, and run the application:

dev@ubuntu:~/HelloWorld$ dotnet runHello, World!Note

The actual output you see depends on the programming language chosen because the console templates have slightly different text. The above output is from the C# template, the F# template would result in Hello from F#, and the VB template would result in Hello World! (without the ,).

Publishing the .NET project¶

The dotnet run command is useful for development when you have a .NET SDK installed. But realistically, you want to distribute your application and run it on a system where just a .NET runtime is installed. To do that, use the dotnet publish command:

dev@ubuntu:~/HelloWorld$ dotnet publishRestore complete (0.7s) HelloWorld succeeded (1.7s) → bin/Release/net9.0/publish/ Build succeeded in 2.7sAs shown by the terminal output, in this case (using .NET 9) the build output is located in bin/Release/net9.0/publish/. This directory would also contain all dependencies (but in this case, there aren’t any). You can copy this directory to the target system and run the application with:

dotnet HelloWorld.dll

This directory also contains a HelloWorld file. This is a wrapper that is able to search for a compatible .NET runtime on the target system and use that to invoke the HelloWorld.dll binary. So, you can also run your application just by executing:

HelloWorld

Finally, there is also a file called HelloWorld.pdb available in the publish directory. This is the PDB debug symbol file for your application, which is not a required file to run the application, but is useful when an error happens and you need to debug your code.

Debugging the .NET project¶

The .NET tooling does not include a debugger; therefore, to debug a .NET application, you need to either use a development environment that includes a .NET debugger, such as Visual Studio Code or JetBrains Rider (see Setting up a .NET IDE for a list of available development environments for .NET), or install a compatible standalone debugger, such as the open-source Samsung .NET debugger.

Regardless of your choice, once you learn to use a debugger in one environment, the knowledge should transfer to whichever other environment you might encounter in the future. For the purposes of this tutorial, we will walk through how to use the .NET debugger available in Visual Studio Code.

Preparing a debugging session¶

First, install Visual Studio Code:

sudo snap install --classic code

Open the Hello World project created in the previous steps with Visual Studio Code by running the following command from within the project root directory.

code .

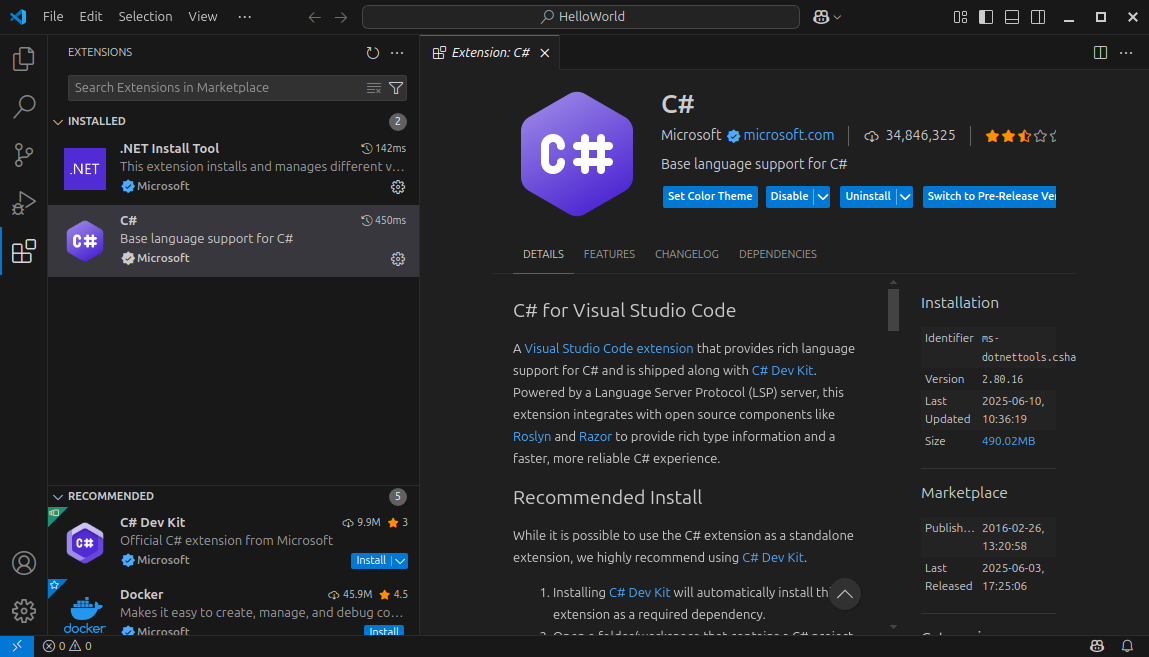

Make sure to have the C# language support extension installed to have access to the debugger.

Now, replace the content of Program.cs with the following code block:

var names = new List<string> { "Alice", "Bob", "Charlie" };

var index = 0;

while (index < names.Count)

{

index++;

Console.WriteLine($"Hello, {names[index]}");

}

Our goal with this piece of code is to build a list of names – Alice, Bob, and Charlie – then greet each one with “Hello” within the while loop. However, running this code shows that it is not working as expected:

dev@ubuntu:~/HelloWorld$ dotnet runHello, BobHello, CharlieUnhandled exception. System.ArgumentOutOfRangeException: Index was out of range. Must be non-negative and less than the size of the collection. (Parameter 'index') at System.Collections.Generic.List`1.get_Item(Int32 index) at Program.<Main>$(String[] args) in /home/ubuntu/HelloWorld/Program.cs:line 8Two problems appeared:

The first name of the list, Alice, is skipped, followed by a

Hello, Bob, thenHello, Charlie.An unhandled exception of type

System.ArgumentOutOfRangeExceptionhappens. According to the error message, we are trying to access an index that does not exist in the collection.

Let’s debug.

Debugging with VS Code¶

To debug a .NET application with Visual Studio Code, we need to create a launch profile. VS Code can create one automatically by clicking the Run and Debug icon, then the Run and Debug button, and selecting the .NET 5+ and .NET Core item from the menu that pops up.

With a launch profile created, go back to the Run and Debug section and click the little Play icon to start debugging the application. You will see that the exception is thrown on line 8, during the Console.WriteLine call.

By analyzing the Variables window, we see that the names variable has three items, but our index variable is already at 3. In .NET, arrays are indexed starting at 0, which means that the current index is one unit larger than the collection size. That explains the ArgumentOutOfRangeException being thrown.

The issue is that we are incrementing the index variable before accessing the names collection. Since the index variable is first assigned to 0, the first increment brings it to 1, making the program greet names starting from the second one – this is a classic off-by-one error. We fix this by moving index++ one line down. Running the program again shows no errors:

Stepping over code¶

Another great use of debuggers is the ability to step through code line by line. This is possible by setting breakpoints in the code. A breakpoint indicates to the debugger that, when running the program, it should pause execution at that specific line. This is especially useful when you, as the developer, want to understand the behavior of your code at one specific point.

To set a breakpoint in Visual Studio Code, hover the mouse over the blank space to the left of the line numbers and click the line you want to set the breakpoint in. A red dot should appear indicating that a breakpoint is now set.

Let’s go ahead and set a breakpoint on line 6:

Now, running the debugger should pause the execution of the program whenever it hits that specific line of code. You can analyze current variable values in the Variables window, see the call stack of the program at that specific line in the Call Stack window, and so on.

Clicking the Step Over icon, or pressing F10, should also let you execute the code line by line and watch how the program behaves in “slow motion”. For example, let’s step over the Console.WriteLine instruction, which should print Hello, Alice to the output console.

The index variable holds the value 0 at that specific point in time. Stepping over the variable increment instruction on line 7 should now bring index to 1.

To continue execution as usual, click the Continue button, or F5, and the program should now execute until it hits the next breakpoint. As we’ve set one inside the while loop, it stops again at the next iteration. To remove the breakpoint, clicking the red dot again, then click Continue to let the program resume and finish execution.

Stepping into code¶

Another feature of debuggers is the ability to step into functions as they are called. As an example, let’s create a function called SayHello, which prints a greeting for whichever name is passed as a parameter. Then, instead of calling Console.WriteLine from within the while loop, we call SayHello.

var names = new List<string> { "Alice", "Bob", "Charlie" };

var index = 0;

while (index < names.Count)

{

SayHello(names[index]);

index++;

}

void SayHello(string name)

{

Console.WriteLine($"Hello, {name}");

}

Setting a breakpoint on line 6 should allow us to pause the execution right before calling the SayHello function.

Now, instead of stepping over this line, we step into it by clicking Step Into, or F11, which should allow us to go into the SayHello function and step over its implementation.

Stepping into .NET code¶

When debugging, stepping into functions within your own code is straightforward, as the debugger has direct access to the source. However, stepping into functions from external libraries or .NET itself requires debug symbols, specifically PDB files.

This is the case if you want to step into Console.WriteLine itself, for example. Clicking Step Into when the debugger hits that line simply steps over it, as the debugger does not have the necessary symbols for the library that provides that function.

However, if you install .NET from the Ubuntu archive packages, you can also install matching .NET debug symbols packages that contain PDB files for the .NET SDK, Runtime, and ASP.NET Core Runtime. With these packages installed, debuggers are able to step into functions defined within .NET itself.

Let’s set a breakpoint at Console.WriteLine on line 12. Make sure to disable Just My Code in your debug launcher; otherwise, the debugger would not step into framework code. To do that, add "justMyCode": false to your launch.json profile:

Alternatively, you can also disable Just My Code globally in the VS Code Settings. Look for the csharp.debug.justMyCode option and uncheck it.

Now, run the debugger:

If we step into that function, or F11, we go into the Concat function implementation, which is responsible for joining our Hello, string with the name variable.

Let’s go ahead and step out of this function, since we want to look into the implementation of Console.WriteLine instead. Click Step Out, or Shift+F11, and the debugger takes us back to Console.WriteLine again – stepping out means “execute the rest of this function and go back to where its value is returned”.

Now, Step Into it again, and the debugger should take us right to the implementation of the WriteLine function itself.

You can keep stepping into the many functions that make up Console.WriteLine to better understand how it works internally.