DNS Security Extensions (DNSSEC)¶

DNSSEC is a security extension for the Domain Name System (DNS). DNS is a mapping between names and Internet Protocol (IP) addresses, allowing the use of friendly names instead of sequences of numbers when reaching web sites. Additionally, it stores extra information about a given domain, such as:

who the point of contact is

when it was last updated

what are the authoritative name servers for the domain

what are the mail exchangers for the domain (i.e., which systems are responsible for email for this domain)

how host names are mapped to IP addresses, and vice-versa

what information about other services, such as kerberos realms, LDAP servers, etc (usually on internal domains only) are there

and more

When DNS was first conceived, security wasn’t a top priority. At its origins, DNS is susceptible to multiple vulnerabilities, and has many weaknesses. Most of them are a consequence of spoofing: there is no guarantee that the reply you received to a DNS query was not tampered with or that it came from the true source.

This is not news, and other mechanisms on top of DNS and around it are in place to counteract that weakness. For example, the famous HTTPS padlock that can be seen when accessing most websites nowadays, which uses the TLS protocol to both authenticate the website, and encrypt the connection. It doesn’t prevent DNS spoofing, and your web browser might still be tricked into attempting a connection with a fraudulent website, but the moment the TLS certificate is inspected, a warning will be issued to the user. Depending on local policies, the connection might be even immediately blocked. Still, DNS spoofing is a real problem, and TLS itself is subject to other types of attacks.

What is it?¶

DNSSEC, which stands for Domain Name System Security Extensions, is an extension to DNS that introduces digital signatures. This allows each DNS response to be verified for:

integrity: The answer was not tampered with and did not change during transit.

authenticity: The data came from the true source, and not another entity impersonating the source.

It’s important to note that DNSSEC, however, will NOT encrypt the data: it is still sent in the clear.

DNSSEC is based on public key cryptography, meaning that every DNS zone has a public/private key pair. The private key is used to sign the zone’s DNS records, and the corresponding public key can be used to verify those signatures. This public key is also published in the zone. Anyone querying the zone can also fetch the public key to verify the signature of the data.

A crucial question arises: How can we trust the authenticity of this public key? The answer lies in a hierarchical signing process. The key is signed by the parent zone’s key, which, in turn, is signed by its parent, and so on, forming the “chain of trust”, ensuring the integrity and authenticity of DNS records. The root zone keys found at the root DNS zone are implicitly trusted, serving as the foundation of the trust chain.

The public key cryptography underpinning SSL/TLS operates in a similar manner, but relies on Certificate Authority (CA) entities to issue and vouch for certificates. Web browsers and other SSL/TLS clients must maintain a list of trusted CAs, typically numbering in the dozens. In contrast, DNSSEC simplifies this process by requiring only a single trusted root zone key.

For a more detailed explanation of how the DNSSEC validation is performed, please refer to the Simplified 12-step DNSSEC validation process guide from ISC.

New Resource Records (RRs)¶

DNSSEC introduces a set of new Resource Records. Here are the most important ones:

RRSIG: Resource Record Signature. Each RRSIG record matches a corresponding Resource Record, i.e., it’s the digital cryptographic signature of that Resource Record.

DNSKEY: There are several types of keys used in DNSSEC, and this record is used to store the public key in each case.

DS: Delegation Signer. This stores a secure delegation, and is used to build the authentication chain to child DNS zones. This makes it possible for a parent zone to “vouch” for its child zone.

NSEC, NSEC3, NSEC3PARAM: Next Secure record. These records are used to prove that a DNS name does not exist.

For instance, when a DNSSEC-aware client queries a Resource Record that is signed, the corresponding RRSIG record is also returned:

$ dig @1.1.1.1 +dnssec -t MX isc.org

; <<>> DiG 9.18.28-0ubuntu0.24.04.1-Ubuntu <<>> @1.1.1.1 +dnssec -t MX isc.org

; (1 server found)

;; global options: +cmd

;; Got answer:

;; ->>HEADER<<- opcode: QUERY, status: NOERROR, id: 51256

;; flags: qr rd ra ad; QUERY: 1, ANSWER: 3, AUTHORITY: 0, ADDITIONAL: 1

;; OPT PSEUDOSECTION:

; EDNS: version: 0, flags: do; udp: 1232

;; QUESTION SECTION:

;isc.org. IN MX

;; ANSWER SECTION:

isc.org. 300 IN MX 5 mx.pao1.isc.org.

isc.org. 300 IN MX 10 mx.ams1.isc.org.

isc.org. 300 IN RRSIG MX 13 2 300 20241029080338 20241015071431 27566 isc.org. LG/cvFmZ8jLz+CM14foaCtwsyCTwKXfVBZV2jcl2UV8zV79QRLs0YXJ3 sjag1vYCqc+Q5AwUi2DB8L/wZR6EJQ==

;; Query time: 199 msec

;; SERVER: 1.1.1.1#53(1.1.1.1) (UDP)

;; WHEN: Tue Oct 22 16:44:33 UTC 2024

;; MSG SIZE rcvd: 187

Other uses¶

DNSSEC makes it more attractive and secure to store other types of information in DNS zones. Although it has always been possible to store SRV, TXT and other generic records in DNS, now these can be signed, and can thus be relied upon to be true. A well known initiative that leverages DNSSEC for this purpose is DANE: DNS-based Authentication of Named Entities (RFC 6394, RFC 6698, RFC 7671, RFC 7672, RFC 7673).

For example, consider a scenario where SSH host keys are stored and secured in DNS using DNSSEC. Rather than manually verifying a host key fingerprint, the verification process could be automated using DNSSEC and the SSHFP Resource Record published in the DNS zone for that host. OpenSSH already supports this feature through the VerifyHostKeyDNS configuration option.

Where does the DNSSEC validation happen?¶

DNSSEC validation involves fetching requested DNS data, retrieving their corresponding digital signatures, and cryptographically verifying them. Who is responsible for this process?

It depends.

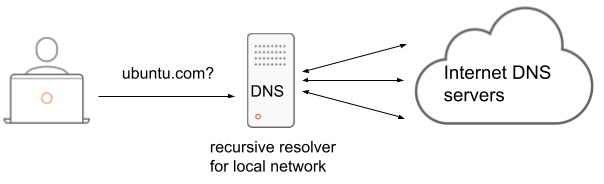

Let’s analyze the simple scenario of a system on a local network performing a DNS query for a domain.

Here we have:

An Ubuntu system, like a desktop, configured to use a DNS server in the local network.

A DNS server configured to perform recursive queries on behalf of the clients from the local network.

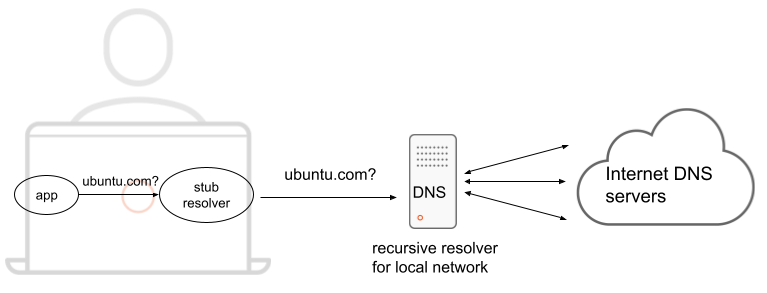

Let’s zoom in a little bit on that Ubuntu system:

To translate a hostname into an IP address, applications typically rely on standard glibc functions. This process involves a stub resolver, often referred to as a DNS client. A stub resolver is a simple client that doesn’t perform recursive queries itself; instead, it delegates the task to a recursive DNS server, which handles the complex query resolution.

In Ubuntu, the default stub resolver is systemd-resolved. That’s a daemon, running locally, and listening on port 53/udp on IP 127.0.0.53. The system is configured to use that as its nameserver via /etc/resolv.conf:

nameserver 127.0.0.53

options edns0 trust-ad

This stub resolver has its own configuration for which recursive DNS servers to use. That can be seen with the command resolvectl. For example:

Global

Protocols: -LLMNR -mDNS -DNSOverTLS DNSSEC=no/unsupported

resolv.conf mode: stub

Link 12 (eth0)

Current Scopes: DNS

Protocols: +DefaultRoute -LLMNR -mDNS -DNSOverTLS DNSSEC=no/unsupported

Current DNS Server: 10.10.17.1

DNS Servers: 10.10.17.1

DNS Domain: lxd

This configuration is usually provided via DHCP, but could also be set via other means. In this particular example, the DNS server that the stub resolver (systemd-resolved) will use for all queries that go out on that network interface is 10.10.17.1. The output above also has DNSSEC=no/unsupported: we will get back to that in a moment, but it means that systemd-resolved is not performing the DNSSEC cryptographic validation.

Given what we have:

an application

stub resolver (“DNS client”)

recursive DNS server in the local network

several other DNS servers in the internet that will be queried by our recursive DNS server

Where does the DNSSEC validation happen? Who is responsible?

Well, any DNS server can perform the validation. Let’s look at two scenarios, and what it means in each case.

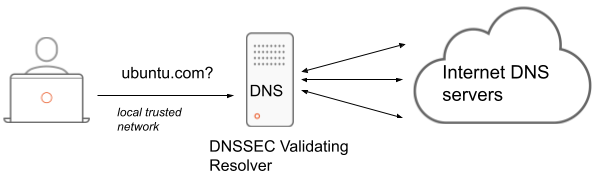

Validating Resolver¶

When a recursive DNS server is also performing DNSSEC validation, it’s called a Validating Resolver. That will typically be the DNS server on your local network, at your company, or in some cases at your ISP.

This is the case if you install the BIND9 DNS server: the default configuration is to act as a Validating Resolver. This can be seen in /etc/bind/named.conf.options after installing the bind9 package:

options {

...

dnssec-validation auto;

...

};

A critical aspect of this deployment model is the trust in the network segment between the stub resolver and the Validating Resolver. If this network is compromised, the security benefits of DNSSEC can be undermined. While the Validating Resolver performs DNSSEC checks and returns only verified responses, the response could still be tampered with on the final (“last mile”) network segment.

This is where the trust-ad setting from /etc/resolv.conf comes into play:

nameserver 127.0.0.53

options edns0 trust-ad

The trust-ad setting is documented in the resolv.conf(5) manpage. It means that the local resolver will:

Set the

adbit (Authenticated Data) in the outgoing queries.Trust the

adbit in the responses from the specified nameserver.

When the ad bit is set in a DNS response, it means that DNSSEC validation was performed and successful. The data was authenticated.

Specifying trust-ad in /etc/resolv.conf implies in these assumptions:

The 127.0.0.53 name server is trusted to set the

adflag correctly in its responses. If it performs DNSSEC validation, it is trusted to perform this validation correctly, and set theadflag accordingly. If it does not perform DNSSEC validation, then theadflag will always be unset in the responses.The network path between localhost and 127.0.0.53 is trusted.

When using systemd-resolved as a stub resolver, as configured above, the network path to the local DNS resolver is inherently trusted, as it is a localhost interface. However, the actual nameserver used is not 127.0.0.53; it depends on systemd-resolved’s configuration. Unless local DNSSEC validation is enabled, systemd-resolved will strip the ad bit from queries sent to the Validating Resolver and from the received responses.

This is the default case in Ubuntu systems.

Another valid configuration is to not use systemd-resolved, but rather point at the Validating Resolver of the network directly, like in this example:

nameserver 10.10.17.11

options edns0 trust-ad

The trust-ad configuration functions similarly to the previous scenario. The ad bit is set in outgoing queries, and the resolver trusts the ad bit in incoming responses. However, in this case, the nameserver is located at a different IP address on the network. This configuration relies on the same assumptions as before:

The 10.10.17.11 name server is trusted to perform DNSSEC validation and set the

adflag accordingly in its responses.The network path between localhost and 10.10.17.11 is trusted.

As these assumptions have a higher chance of not being true, this is not the default configuration.

In any case, having a Validating Resolver in the network is a valid and very useful scenario, and good enough for most cases. And it has the extra benefit that the DNSSEC validation is done only once, at the resolver, for all clients on the network.

Local DNSSEC validation¶

Some stub resolvers, such as systemd-resolved, can perform DNSSEC validation locally. This eliminates the risk of network attacks between the resolver and the client, as they reside on the same system. However, local DNSSEC validation introduces additional overhead in the form of multiple DNS queries. For each DNS query, the resolver must fetch the desired record, its digital signature, and the corresponding public key. This process can significantly increase latency, and with multiple clients on the same network request the same record, that’s duplicated work.

In general, local DNSSEC validation is only required in more specific secure environments.

As an example, let’s perform the same query using systemd-resolved with and without local DNSSEC validation enabled.

Without local DNSSEC validation. First, let’s show it’s disabled indeed:

$ resolvectl dnssec

Global: no

Link 44 (eth0): no

Now we perform the query:

$ resolvectl query --type=MX isc.org

isc.org IN MX 10 mx.ams1.isc.org -- link: eth0

isc.org IN MX 5 mx.pao1.isc.org -- link: eth0

-- Information acquired via protocol DNS in 229.5ms.

-- Data is authenticated: no; Data was acquired via local or encrypted transport: no

-- Data from: network

Notice the Data is authenticated: no in the result.

Now we enable local DNSSEC validation:

$ sudo resolvectl dnssec eth0 true

And repeat the query:

$ resolvectl query --type=MX isc.org

isc.org IN MX 5 mx.pao1.isc.org -- link: eth0

isc.org IN MX 10 mx.ams1.isc.org -- link: eth0

-- Information acquired via protocol DNS in 3.0ms.

-- Data is authenticated: yes; Data was acquired via local or encrypted transport: no

-- Data from: network

There is a tiny difference in the output:

-- Data is authenticated: yes

This shows that local DNSSEC validation was applied, and the result is authenticated.

What happens when DNSSEC validation fails¶

When DNSSEC validation fails, how this error is presented to the user depends on multiple factors.

For example, if the DNS client is not performing DNSSEC validation, and relying on a Validating Resolver for that, typically what the client will see is a generic failure. For example:

$ resolvectl query www.dnssec-failed.org

www.dnssec-failed.org: resolve call failed: Could not resolve 'www.dnssec-failed.org', server or network returned error SERVFAIL

The Validating Resolver logs, however, will have more details about what happened:

Oct 22 17:14:50 n-dns named[285]: validating dnssec-failed.org/DNSKEY: no valid signature found (DS)

Oct 22 17:14:50 n-dns named[285]: no valid RRSIG resolving 'dnssec-failed.org/DNSKEY/IN': 68.87.68.244#53

...

Oct 22 17:14:52 n-dns named[285]: broken trust chain resolving 'www.dnssec-failed.org/AAAA/IN': 68.87.72.244#53

In contrast, when DNSSEC validation is being performed locally, the error is more specific:

$ sudo resolvectl dnssec eth0 true

$ resolvectl query www.dnssec-failed.org

www.dnssec-failed.org: resolve call failed: DNSSEC validation failed: no-signature

But even when the validation is local, simpler clients might not get the full picture, and still just return a generic error:

$ host www.dnssec-failed.org

Host www.dnssec-failed.org not found: 2(SERVFAIL)

Further reading¶

RFC 4255 - Using DNS to Securely Publish Secure Shell (SSH) Key Fingerprints